BESTIARIES are a particularly characteristic product of medieval England, and give a unique insight into the medieval mind. Richly illuminated and lavishly produced, they were luxury objects for noble families. Their three-fold purpose was to provide a natural history of birds, beasts and fishes, to draw moral examples from animal behaviour (the industrious bee, the stubborn ass), and to reveal a mystical meaning – the phoenix, for instance, as a symbol of Christ’s resurrection.

Bestiaries drew their inspiration from classical sources, to which were added very early Christianised versions of the work of natural historians. Thus, unreal animals and whimsical names derive from travellers’ tales, from the symbolism of oriental art, and from misunderstood observations of animal behaviour, giving form to the mysterious unicorn, the man-eating manticore, the phoenix-phenomenon of ‘anting’ in birds. Mixed with this are descriptions of familiar and readily recognisable creatures. It is the combination of engaging text and vividly depicted animal world, put’ together with an entirely serious purpose, that makes bestiaries objects of such fascination.

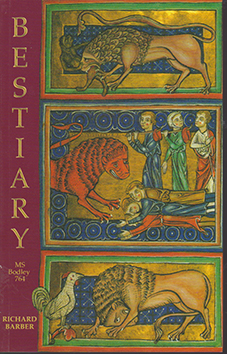

This Bestiary, MS. Bodley 764 (in the Bodleian Library in Oxford), was produced around the middle of the thirteenth century, and there are some clues to the patron who commissioned it in the heraldry incorporated in the artist’s work. Whomever it was, the resulting manuscript is of singular beauty and interest. The lively illustrations have the freedom and naturalistic quality of the later Gothic style, and make dazzling use of colour. This book reproduces the 136 illuminations to the same size and in the same place as the original manuscript, fitting the text around them. Richard Barber’s translation from the original Latin is a delight to read, reflecting the manuscript’s serious intent with a feeling for the underlying charm of the beasts as seen by the medieval world.

A beautiful facsimile of an original which is now in the Bodleian Library. It was produced during the first half of the 13th century; both artist and patron are unknown, but Barber’s excellent translation from the Latin original makes for fascinating reading about beasts, real and imaginary, of the medieval world. EVENING STANDARD

Beautifully reproduced, the illustrations are given their exact positions in the original Bodleian manuscript; the elegantly translated text is a mixture of medieval reality, Christian symbolic explanation and the literally fabulous. COUNTRY LIFE